If 95%+ of comments have been rated as "fine", does the site deserve its reputation of "unwelcoming"? Do we still need to focus on it?

(Originally published on meta Stack Exchange by Jon Ericson.)

I’d wager that whether 95% seems low or high (or just right) depends on your prior assumptions. Perhaps the most important sentence of the blog post reads:

[We] as employees learned that we don’t always perceive problems in the same way as other members of our community.

Employees as a group rated more comments as unwelcoming or abusive than users. Based on our priors, the user ratings seem somewhat more optimistic about the current state of comment friendliness. Perhaps the reason we rated comments as less welcoming than other groups is because we were primed to see negative comments because it’s a common complaint about the site. It is one factor in why Stack Overflow’s growth has leveled off and is a problem we’ve been eager to solve for years.

But what is an acceptable level of unwelcoming comments? Perhaps you don’t see any particular problem with the tone of the network. In that case, the current level is fine. I guess. Conversely, if you are concerned that comments are too harsh, the current level is too high. My guess is that most people who spend time on the site would estimate that somewhere between 90-99% of comments are “fine”. Generally we all agree Stack Exchange comments tend to be better than comments on other sites. So finding out that 95% of comments are fine won’t change our prior understanding of the “welcomingness” of the site. Neither would 91.8%, for that matter.

So what’s an objectively defined level of too many unwelcoming comments? I think the answer very much depends on whether you care about the network being a permanent resource or if you are willing for the network to shut down in a few decades. This might seem overly dramatic, but I encourage you to walk down this mental path with me. (And please excuse me for focusing on Stack Overflow in the beginning. I’ll get to the rest of the network near the end.)

Usenet: a cautionary tale

I got interested in newsgroups when I started programming full time in 1999. I distinctly remember an article by Jon Udell that opened my eyes to the possibility of what we used to call groupware. It was already a well-matured system that let ordinary programmers help each other. It was also “overwhelmed with spam, smut and nonsense”. Fortunately, some groups (notably the the Big 8) were relatively free of these distractions. While some groups relied on moderation, many thrived simply by using social pressure. Obnoxious users would be reprimanded by Usenet grognards. One strict rule was to ignore certain troublemakers (trolls). There were essentially no other controls to keep quality high and noise low.

Stack Overflow essentially made Usenet irrelevant for finding answers to programming questions. There are a number of reasons:

- Q&A is a better format for knowledge propagation than branching discussions.

- Stack Overflow content has always been favored by search engines.

- The reputation system encouraged enlightened self-interest.

- Features like voting and question closing surfaced useful content.

But also Stack Overflow had not yet developed a reputation for harshness. Since there weren’t any rules in the beginning except those created by the system, it felt safer for my generation of programmers than Usenet with its killfiles and exhortations not to feed trolls. For people like me it was an enormous opportunity to forge new rules and a new way of interaction.

So Usenet lost out to a superior product and also to a fresh culture. After 10+ years, that culture is not so fresh anymore. It’s no longer possible for a handful of users to shape the way people interact. While I think we’ve mostly ended up in a good place, our interactions with each other are far from perfect. For the moment, I don’t see a viable alternative to Stack Overflow. However, when it does arrive, I’m certain the opportunity to start over will be attractive to many existing users.

Artificial societies

We might pick 0 unwelcoming comments as an objective goal. The trouble with this zero-tolerance approach is that it leads to shifting standards. This is how we end up with a student arrested for bringing a clock to school. It’s also not entirely clear how much of the problem is related to public perception and how much is related to harsh comments that still exist on the site. It could be that we could eliminate unwelcome comments and still be seen as too harsh.

On the other hand, it’s obvious that there is some level at which unwelcoming comments discourage users from using the site and actively drive them away. Everybody has their own level of tolerance for unwelcoming behavior, so we need to look at the effects on the society has a whole. It’s not the sort of thing we can solve with a vote or using our gut.

To illustrate the current situation, I created an agent-based model of how users might respond to a potentially unwelcoming environment. I built the model based on Shamus Young’s Philosophy of Moderation. He postulates that there are three types of users:

- Unshakable kind people,

- Unrepentantly harsh people and

- Normal folks who adjust to the current tone they see around them.

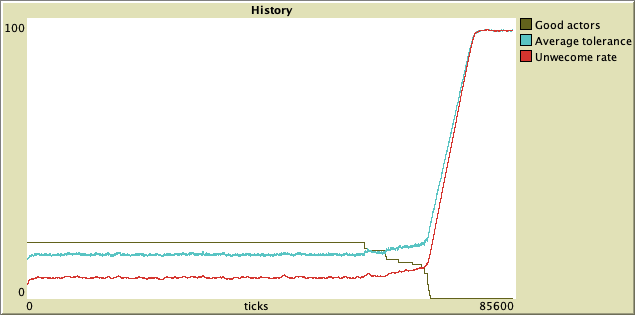

I built a very simple model that you can try out. (Click the “Model Info” arrow for a detailed description and “NetLogo Code” for the source code.) It assumes that kind people will always raise the level of discourse, but will leave if there are too many unwelcoming comments. Harsh people influence the environment by increasing unwelcoming comments and normal users adapt to the average level of their neighborhood. The result is an very stable situation that seems entirely sustainable for a long period of time. But every now and then a user with low tolerance for unwelcome comments will leave the site and when enough have, it will start a cascading failure case:

This is probably a good time to say I started writing the model late last week and this is the first time I’m sharing it with anyone. This by no means motivated the Welcome Wagon project and is my own idiosyncratic way of looking at the world. But I think most of us in the company agree that our public sites, and Stack Overflow in particular, are at risk of cultural calcification. If we become too insular, the next generation of programmers could very well pass us by.

The critical number in the model is the level of unwelcoming comments that will cause people to start to leave. I estimated that people who have high standards for tone will leave if 20% or more of the comments they see are snarky. That can happen from time to time even if 90% or more of comments globally are just fine. So I’m not really any closer to knowing what the “right” level is, but we can’t necessarily feel safe at the current level.

Chat: a cautionary tale

This pattern usually takes a long time to develop in the model. Without examples, it’s difficult to validate the model. We’ve had a few sites fail dramatically in their first few weeks because of increasingly crase content. The cases I recall involved “Sexuality” sites that started off poorly and quickly descended from there. We finally got a site that works for this topic by expanding to Interpersonal Skills in general and having a team of hardworking users uphold certain standards. The model suggests that if these users left, it wouldn’t take long for the site to fall into 4chan territory.

You might intuit that it’s a natural consequence of the topic matter. But we’ve see the same pattern several chat rooms on the network, including several language-specific rooms on Stack Overflow. Everytime this comes up, we discover that users serious about civil discourse have given up on the room and the users who remain believe it’s fine for a room to have a culture of coarse jokes and irreverent commentary. In other words, my simple model captures a common failure case in chat. Since chat is more fluid than onsite comments, it’s not surprising we’d see these problems develop more quickly in that medium.

What about content?

As I thought about the model for unwelcoming comments, it occured to me that it would work just as well to model post quality. The dynamics seem similar in that some people have high standards, others have low or no standards, and the majority will tend to the current level of quality they see around them. What happens in the people with high standards start to leave? Well, I expect quality will fall off a cliff at some point.

So why shouldn’t that be the priority? Well, the first reason is that it has been since the very first question was asked on the site. If you look at the tools we have for controlling content, they are quite varied: voting, closing, locking, protecting, editing, deleting, reviewing and quality filters. At least one of these tools ought to address quality problems when they crop up. Our tools for dealing with unwelcome comments (flags, deletion and suspension) are less flexible.

My second reason is more nuanced: quality is contextual. When I read complaints about quality on the site, it’s not uncommon for people to focus not on obviously junk content, but on posts that have more subtle flaws. Maybe the code should be checking for system call errors or avoid a certain security flaw or stop using global variables for everything. It’s not so much that answers are wrong as that they fail to exemplify excellence in the craft of programming. It might be acceptable to have such code in a throw-away script, but it shouldn’t be used in a public answer where unsuspecting new programmers might learn bad habits.

One of the things we’ve learned through user research is that programmers read more than just the top answer to a question. This is good because it’s not uncommon to see the top two answers of popular questions be 1) an ultra-pragmatic answer that gives a solution and 2) a detailed answer explaining the nuances readers might come across. (Randomly chosen example: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/503093/how-do-i-redirect-to-another-webpage) It might be that the best answer for a particular situation is the quick and dirty one. But there’s also plenty of room to add another detailed answer that demonstrates the best we have to offer.

There’s one more reason I think we should be working on more welcoming comments: we haven’t given up on quality. Right now, we are testing custom question lists, which will help people find questions to answer. Also, we will be testing the next iteration of the ask a question wizard soon. And there are a few more projects in the early stages of discovery which ought to help users produce better content.

Everyone codes now

Our annual survey reported:

Each month, about 50 million people visit Stack Overflow to learn, share, and build their careers. We estimate that 21 million of these people are professional developers and university-level students.

So who are the ~29 million people who visit Stack Overflow and are not developers? Some of them are astronomers who use R, journalists who use Git and Community Managers who use NetLogo to get their jobs done. Every indication is that there will be more non-programmers in the future. I think there are two possible consequences:

- Code that non-programmers use can be less concerned about best practices.

- Non-programmers will need help from programmers to get applications that meet their needs.

When I worked at JPL, I was responsible for processing spectrometer data into useful atmospheric science products. The scientists wrote their algorithms in FORTRAN and provided executables that we ran on global observations. For a few months after launch, everything seemed to be going well. But we started noticing that the science algorithms were taking longer and longer to finish. After some investigation, we discovered the executables were pulling in all the rows in the database into memory and then filtering down to the relevant dataset. Not only was that a lot of unneeded I/O overhead, but the algorithm used to select the data was something like O(n2). So as we added more data, processing took exponentially longer.

Since it was too late to change the science software, we created a

hack: every discrete dataset would go into its own schema and we’d pass

the connection string for that subset schema to the science executables.

Eventually, we built an entire system around that concept that created

schemas from the complete dataset as needed. I would have prefered to

fix the queries so they had a where clause. But my job was

to make everything work, so that’s what I did.

It’s far too late to say that Stack Overflow is for programmers; we already have a majority of non-developers using the content on this site. So the question is how do we accommodate those who are new to the mysteries of code. Yes, we need to be strict about pure junk. (But please don’t use comments.) However when confronted with code that, say, will never scale properly, we ought to kindly and helpfully point that out. This is, afterall, a teaching opportunity.

The diversity of Stack Exchange

Ok, let’s get real. The immediate reason we started the Welcome Wagon is that our annual survey annually reveals we don’t have a very diverse user base on Stack Overflow. There are good reasons to worry about that even if you don’t care about bad PR. Like most companies, we do care about getting good press, so this is likely to be one of our priorities for as long as it is seen as a problem.

We have a lot more diversity sitting just outside programmer Jerusalem. The network is still male-dominated, of course. But the sites themselves host an incredible variety of topics beyond programming. It demonstrates that the Q&A format can be welcoming to a variety of people. I’m incredibly proud to be a part of these communities and we ought to do what we can to avoid the sort of catastrophic collapse that my model suggests is possible for any of our sites.

Please direct comments to the original post.