Sourdough and the art of tending a culture

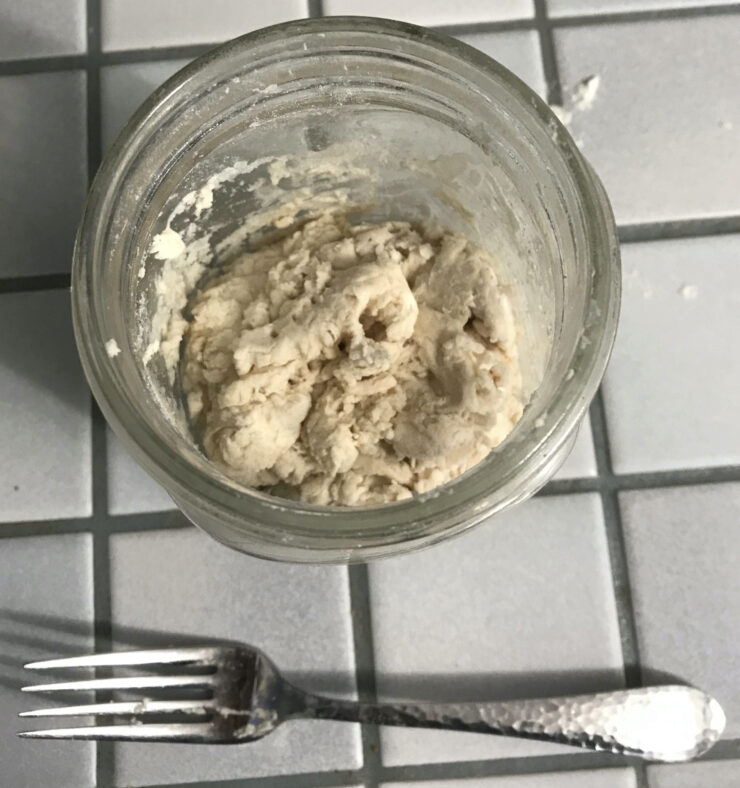

I let my sourdough starter die several years ago because I just didn’t have the energy to bake. Last week I got the urge again and got a starter going. My previous starter was from a family culture I brought from Idaho, so I never started a culture myself. On day one, I mixed equal weight water and flour into a jar. Since water is much denser, that works out to roughly double the flour by volume. For simplicity, I just use a half cup of flour and a quarter cup of water.1 Then I waited. For my flour, I have some whole wheat flour that got lost in my move. It’s not rancid yet, but I wouldn’t want to use it in bread. Perfect for my starter though. The yeast and bacteria that make up a sourdough culture don’t care what my flour tastes like.

Nothing happened in the first 24 hours. Just a lump of dough to look at. But at a microscopic level, the moisture is beginning to revive yeast spores that are found in the air and in the flour. I put my starter between the toaster and the oven to encourage them to reproduce.2 Yeast consumes the sugars found in flour to product carbon dioxide (useful for leavening) and alcohol. We use alcohol in drinks, of course, but it also serves as a disinfectant. Brewing was an important discovery for civilization because it provided germ-free hydration. Alcohol in starters fends off most other microbes. But it doesn’t deter lactobacilli, which are bacteria that convert sugars to lactic acid. They thrive in environments with alcohol. Their waste product increases the acidity of the starter and that wards off other microbes too.

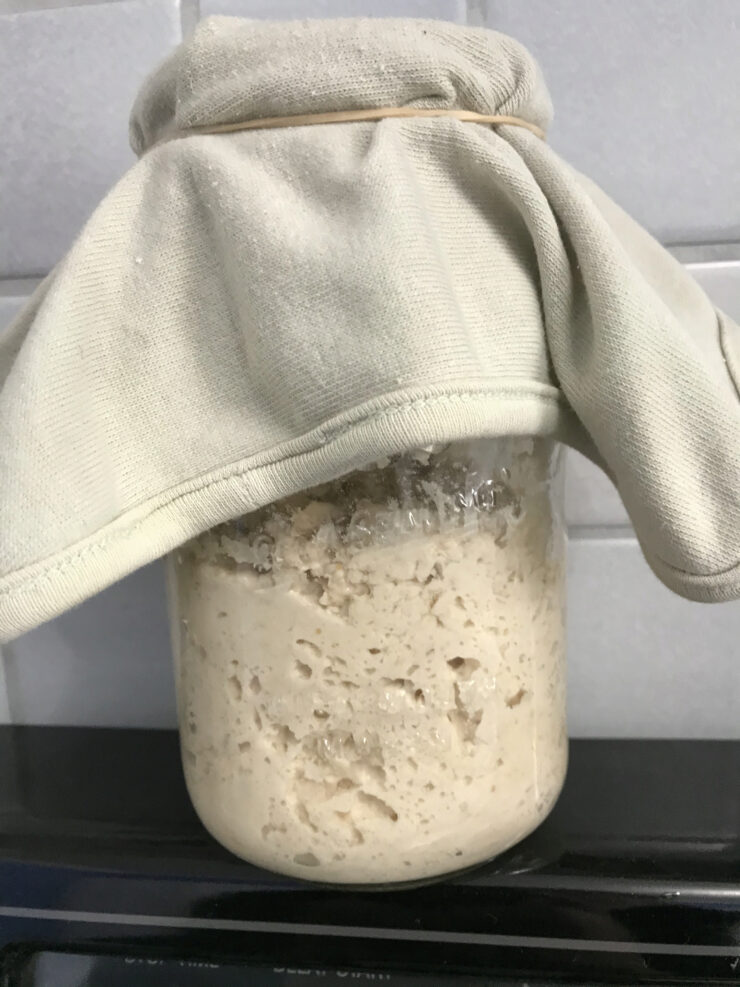

So yeast and lactobacilli work together to create an environment hostile to almost everything else. In addition, the bacteria consume mostly maltose, which is a sugar produced when starches in flour are broken down by an enzyme called amylase. Yeast, as it turns out, produces amylase. It also consumes all the other sugars found in flour such as glucose. Together the yeast and bacteria convert moistened flour into carbon dioxide, alcohol and lactic acid. It’s a symbiotic relationship with one missing piece: a baker. At some point sourdough culture runs out of sugars and starches to digest. And the alcohol and acid can even harm the culture if allowed to accumulate. On its own, the culture would consume itself and the yeast would form spores so that it will survive starvation. Therefore on day 2, I added another equal parts (by weight) flour and water. This allows the yeast and bacteria to thrive. I started to see bubbles of CO2 rising to the top of the starter, which is what I hope to get from tending the culture.

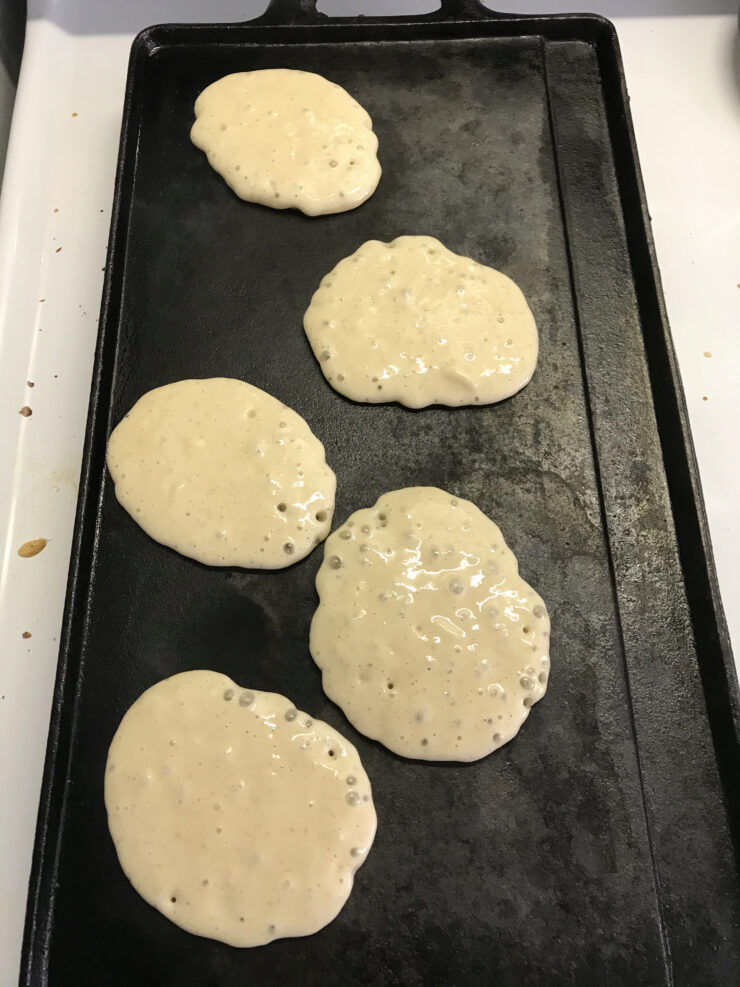

On day 3 I made a batch of pancakes. They don’t need much leavening (and I added some baking powder to help out). Since I’m adding more flour and water to the culture, I’ll need to also take out a fair amount of starter regularly or it will get too large for my jar. Hence pancakes.

The first batch isn’t terribly sour. It’s mostly the bacteria that gives sourdough its unique flavor. Typically it takes a week after reviving a starter to get a stable culture. At the moment, it smells and looks kinda gross before I feed it. The balance isn’t right yet. My pancakes were on the boring side. (We ran out of milk yesterday and nobody has wanted to go to the store for more.) But in a few days I’ll be ready to bake bread. That’s the ultimate goal, of course. That and waffles, pretzels, English muffins, dinner rolls, etc. and so on.

I used the word “culture” a few times in this thread because that’s the technical term for what a sourdough starter is. It’s a mix of organisms growing together. But we usually think of culture in human terms. It’s the medium in which groups thrive. Successful human cultures are symbiotic. The interdependencies are far more complex than the symbiosis between yeast and bacteria feeding on wheat flour and water.

Think of the complex culture required to produce a TV show, for instance. On the one side there’s an industry full of specialized workers producing 20 to 60 minute sequences of images and sound. On the other are thousands and millions of people with similar cultivated preferences. And in the middle are curators and distribution channels. If we want more of the product (TV shows) we need to have a stable environment so that some people will spend the time needed to be really good at, say, making sound effects. It’s no good learning to do that if the market for that skill dries up.

I’m convinced, by the way, that California has thrived as an entertainment center because it has generous unemployment benefits. When a show ends its run, everyone has a stable source of income while they look for a new gig. It’s not the only possible solution,3 but it works.

All this brings me to online community management and a mistake I’ve seen far too many times: misinterpreting hostility. The easiest way to think of snark, rude comments, grumpiness and so on is that some people are just mean and we should get rid of them.

Now to be clear, some people are mean and we should get rid of them. But that group of people tend to be a small percentage of even unhealthy communities. We call these people trolls and they exist to cause problems. Most of the time they go way beyond the occasional snark. We do need to remove them or they will spoil the culture.

Think back to the yeast and bacteria in sourdough. They produce an environment hostile to other microbes as a natural byproduct of digesting sugars. It’s not because they are being mean; it’s just what they do. Acid and alcohol build up if there’s not enough sugar for growth.

Same thing with communities. People are drawn to a group because they can do things there. It might be to answer questions on Stack Exchange or to find out what SAT scores and GPA are needed to get into a specific school on College Confidential. In some cases people come to a community once or twice and leave. That’s a bit like the flour I add to my starter. In other cases, people don’t leave. They are committed to the community itself. Remembering they are instrumental in this analogy, they are like yeast and bacteria.

It’s easy to dislike the flavor of a community and blame the part of the community that puts a sour taste in your mouth. “I wish all those lactobacilli would just find some other place to go. Why do we allow lactic acid anyway?” It’s a straight line from identifying a perceived problem, spotting the cause and formulating a solution. It’s also a big mistake. If there’s a functional community, it’s likely each part (other than the trolls) serve a useful purpose. Perhaps lactic acid protects the culture somehow?

Originally published on Twitter. I’ve added a few images and footnotes.

I used The Clever Carrot’s sourdough starter recipe. In the past, I’ve use Nancy Silverton’s feeding plan which uses equal volume. That produces a much more liquid starter, obviously. I’m not sure which I will like better, but according to Modernist Cuisine a more liquid starter is more sour.↩︎

The microbes, not the appliances.↩︎

There’s also a union, which is the traditional way for people skilled at a particular craft to preserve that knowledge.↩︎